I very much

wanted to see the Jimmie Durham retrospective at the Whitney Museum. I’ve

known about Jimmie Durham as an American Indian artist for at least 30 years and his

relocation to Europe in the 1980s seemed a loss for the art world of the United

States. No one I know has heard of him. I’ve seen his work occasionally in

European museums, but it was a surprise that major museums in the United States

would mount a show. There has been some controversy about his

self-identification as American Indian, and that aspect of his work was not emphasized

in the exhibition until near the end. That made sense because his work address

many subjects and aspects of his identity.

Although I was eager to see the

exhibition, I expected to be disappointed because I know Durham makes extensive

use of found objects and thought I would see a lot of abstract constructions of

detritus. In fact, I found the exhibition riveting, fascinating, touching,

amusing, and both personal and universal. The first room captured me with a

video of Durham hacking away at a chunk of obsidian, making an abstract

sculpture from this very hard stone, used to make amazingly sharp tools in

ancient Mexico.

|

| Slash and Burn, 2007 Collection of Mima and Cesar Reyes |

|

| Slash and Burn, detail |

|

| Carnivalesque Shark in Venice, 2015, glass, goat leather, piranha teeth, papier-mache and acrylic paint Collection of Eleanor Heyman Propp |

Because we love Venice and

collect glass, the second object, Carnivalesque

Shark in Venice, 2015 also caught my attention, a glass shark with a

painted carnival mask, which was simply amusing.

|

| The Dangers of Petrification, detail, 1998-2007 |

|

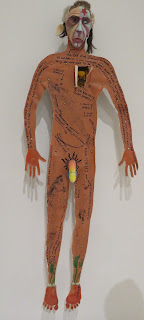

| Malinche Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium |

|

| Malinche, detail |

In another gallery was a

composite portrait labeled as La Malinche, the woman Cortez took up with in

Mexico, considered the ancestor of mixed race Mexicans, mestizos. First planning it as an image of Pocahontas, Durham revised it and added figure

representing Cortez. The face of La Malinche is remarkably expressive,

considering the simple materials and abstracted style used to create it. A detail of it illustrates Holland Cotter's positive NY Times review of the exhibition, which also includes illustrations of many more works in the exhibition.

|

| Wahya, 1984, detail. Bear Skull and more Coll. of Luis H. Francia and Midori Yamamura |

|

| Wahya, 1984 detail of other side |

Then there are the totem-like

constructions employing animal skulls and various found objects. Looking at my

photographs I was stunned by how completely different they are from each side,

as well as how powerfully expressive they are.

|

| I Will Try to Explain, 1970-2012 Private Collection, courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City |

|

| Untitled, 1982, baby buffalo skull, beads, goat leather, hawk feather, shells, acrylic paint Collection Joe Overstreet and Corrine Jennings |

For many of the works the accompanying texts and the context provided by the labels add multiple dimensions to the already sculptural forms. One example is the single skull, remnant of a 1982 installation of elaborated animal skulls, Manhattan Festival of the Dead, with texts urging the gallery visitor to purchase them for $5 each because the work of dead artists goes up in value and the artist is already approaching the life expectancy of an American Indian, and dedicating the works to the members of the American Indian Movement who were killed after the 1973 siege at Wounded Knee as well as to everyone in New York “killed by subways, .38 slugs, needles or desparate [sic] acts, without any proper ceremonies to help their passage and our passage.”

from Six authentic things, 1989, Real Obsidian (Private Collection)

|

| Une etude des etoils, 1995 Collection of Herve Lebrun |

and A Study of Stars, 1995. The little inscription above says "The Cherokee stars have seven points" in French. I particularly liked the computer key and the starleaf gum leaf.

At this point I realized that I

had gone through the exhibition backwards.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment