I very much

wanted to see the Jimmie Durham retrospective at the Whitney Museum. I’ve

known about Jimmie Durham as an American Indian artist for at least 30 years and his

relocation to Europe in the 1980s seemed a loss for the art world of the United

States. No one I know has heard of him. I’ve seen his work occasionally in

European museums, but it was a surprise that major museums in the United States

would mount a show. There has been some controversy about his

self-identification as American Indian, and that aspect of his work was not emphasized

in the exhibition until near the end. That made sense because his work address

many subjects and aspects of his identity.

Although I was eager to see the

exhibition, I expected to be disappointed because I know Durham makes extensive

use of found objects and thought I would see a lot of abstract constructions of

detritus. In fact, I found the exhibition riveting, fascinating, touching,

amusing, and both personal and universal. The first room captured me with a

video of Durham hacking away at a chunk of obsidian, making an abstract

sculpture from this very hard stone, used to make amazingly sharp tools in

ancient Mexico.

|

Slash and Burn, 2007

Collection of Mima and Cesar Reyes |

|

| Slash and Burn, detail |

The first object I looked at was this

one, titled

Slash and Burn, 2007, and

the label provides very helpful context for the work: “While in residence at

the Atelier Calder in the Loire Valley, Durham found a fallen beech tree in

Strasbourg, France. Inspired by its physical traces of history – it had

declarations of love carved into the bark as well as seven bullets from World

War II embedded in it – Durham cut the tree into several planks, which he

incorporated into a series of sculptures including this work. Fascinated by the

patterns and holes created by insects and fungus growth, he chose to accentuate

these natural phenomena by painting them with watercolor. As he has done in a

number of other works throughout his career, here Durham includes text that

directly addresses the viewer and describes his process of embellishing the

beech tree.” The label, the text on the work, and Durham’s additions to the

plank of wood all contribute to the depth of both personal (both his own and

others), natural, and national history the slab evokes. It was difficult to

move away from this very simple object.

|

Carnivalesque Shark in Venice, 2015, glass, goat leather, piranha teeth, papier-mache and acrylic paint

Collection of Eleanor Heyman Propp |

Because we love Venice and

collect glass, the second object, Carnivalesque

Shark in Venice, 2015 also caught my attention, a glass shark with a

painted carnival mask, which was simply amusing.

|

| The Dangers of Petrification, detail, 1998-2007 |

Many of the works are gatherings

of found objects with inscriptions that suggest political issues, artistic

media, or Durham’s personal issues, often all at once, so that they have both

broad and specific context. Sometimes the sculpture or panel composing several

found objects was uninteresting until one read Durham’s descriptions of the

items. For example, I found The Dangers of Petrification, 1998-2007, two vitrines of rocks, labeled as petrified states of

various unlikely items particularly amusing. The objects played with our

assumptions about what things look like, as well as the idea of scientific

collecting and categorizing. The rocks seemed possible as petrified everyday

foods, but it took a particular kind of vision and imagination on the part of

the artist to see them as petrified German black bread, chocolate cake, cheese,

or bacon.

|

Malinche

Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium |

|

| Malinche, detail |

In another gallery was a

composite portrait labeled as La Malinche, the woman Cortez took up with in

Mexico, considered the ancestor of mixed race Mexicans, mestizos. First planning it as an image of Pocahontas, Durham revised it and added figure

representing Cortez. The face of La Malinche is remarkably expressive,

considering the simple materials and abstracted style used to create it. A detail of it illustrates Holland Cotter's positive

NY Times review of the exhibition, which also includes illustrations of many more works in the exhibition.

|

Wahya, 1984, detail. Bear Skull and more

Coll. of Luis H. Francia and Midori Yamamura |

|

| Wahya, 1984 detail of other side |

Then there are the totem-like

constructions employing animal skulls and various found objects. Looking at my

photographs I was stunned by how completely different they are from each side,

as well as how powerfully expressive they are.

|

I Will Try to Explain, 1970-2012

Private Collection, courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City |

In several of the works, Durham’s

inscriptions make them almost literary and certainly biographical, always in an

unprepossessing mode. I Will Try to

Explain, 2007-2012, a rather simple collage, caught me with the sentence

involving the cat skin, but carried through with mention of friends, the

struggle to make good art, and the history of the farmer, the cat, the object

itself, and the artist. It’s almost like poetry.

|

Untitled, 1982, baby buffalo skull, beads, goat leather, hawk feather, shells, acrylic paint

Collection Joe Overstreet and Corrine Jennings |

For many of the works the

accompanying texts and the context provided by the labels add multiple

dimensions to the already sculptural forms. One example is the single skull,

remnant of a 1982 installation of

elaborated animal skulls,

Manhattan Festival of the Dead, with texts urging the gallery visitor to purchase

them for $5 each because the work of dead artists goes up in value and the

artist is already approaching the life expectancy of an American Indian, and

dedicating the works to the members of the American Indian Movement who were

killed after the 1973 siege at Wounded Knee as well as to everyone in New York “killed

by subways, .38 slugs, needles or desparate [sic] acts, without any proper

ceremonies to help their passage and our passage.”

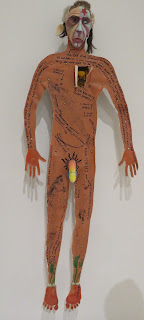

There is a particularly amusing self-portrait with identifying inscriptions, ,

from

Six authentic things, 1989,

Real Obsidian (Private Collection)

|

Une etude des etoils, 1995

Collection of Herve Lebrun |

and A Study of Stars, 1995. The little inscription above says "The Cherokee stars have seven points" in French. I particularly liked the computer key and the starleaf gum leaf.

At this point I realized that I

had gone through the exhibition backwards.

.